landscape

We can

connect to

everything

Israeli

and bring

something

from where

we came,

without

weakening

our identity.

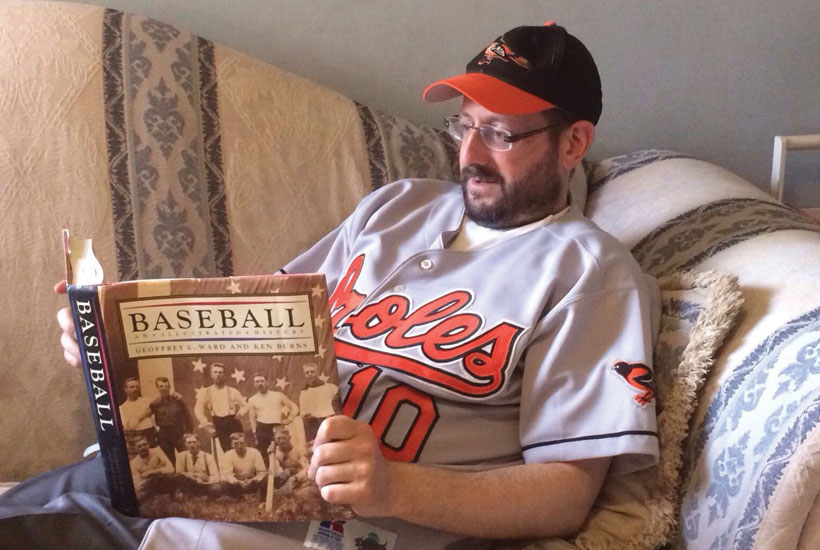

NO SPORT LEFT BEHIND:

THE AMERICAN FAN LIVING IN ISRAEL

by ELLI WOHLGELERNTER

JERUSALEM

W hen American sports fans move to Israel, they often take their love of sports along for the ride. Even after becoming Israeli — fully acculturated and fully embracing the country’s interests, language, politics, and culture — there is one piece they can’t let go of: the crazy way they love American sports.

These former Americans have lived here for 20 or 30 years, have raised their children as Israelis, and have left behind their American lives — except they still passionately follow their Yankees, their Bulls, their Red Wings, or their Dolphins.

American immigrant sports fans face a specific problem in Israel: there is no professional league for three of the four major U.S. sports — baseball, football, and hockey. So, while the immigrant from England can relate to Israeli soccer while still following Manchester United, what team can a sports-mad American follow? Moreover, does their infatuated devotion to the Cubs or Cowboys interfere with becoming 100 percent acculturated?

No, it doesn’t, says Susie Keinon, who does not follow Israeli sports teams but is a loyal fan of her hometown Chicago White Sox.

“We can still hold on to our Israeliness, and it may even enhance our Israeliness,” says Keinon, a psychotherapist who has been living in Israel for 31 years. “We can connect to everything Israeli and bring something from where we came, without weakening our identity. Just the opposite: it can enhance our identity, and help us feel more secure and at ease with both parts — by outwardly saying ‘there is room for both.’”

Keinon says her passion helps her bond with other Americans in Israel. “A few people in our neighborhood understand my interest, and we stop to talk about it at the makolet (local grocery store), or at shul, or on the street,” she says.

Her husband, Herb, a columnist at The Jerusalem Post, says being an American sports fan is a topic of conversation, but he would not go so far as saying it helps him bond with other Americans. “Living here is bond enough,” he says.

One side benefit of having remained a fan of U.S. sports is that it helps stay connected with family back home. Says Herb, “I always speak about sports with my father and brother-in-law.”

What’s difficult for the Keinons and other American sports fans is staying plugged in live — most baseball games begin at 2 A.M. in Israel, though NFL kickoffs on Sunday are at 8 P.M. and 11 P.M.

“We can connect to everything Israeli and bring something from where we came, without weakening our identity. Just the opposite: it can enhance our identity, and help us feel more secure and at ease with both parts...”

“Sleep has always been more important than sports,” says Susie. “During football season, I sometimes stay up a couple of hours later than usual to watch a good game. During baseball season, I generally settle for highlights or [for] watching a game the next day, but not live.”

Unlike in the pre-cable or pre-Internet days, when sports news from North America was difficult to access and real-time scores or play-by-play accounts were virtually unavailable, today’s sports apps make it easy to stay connected. Herb, a former season ticket holder to the Denver Broncos, watches every Broncos game via the NFL’s Game Pass app, which brings him the weekly games on demand.

“I do follow the football season from start to finish,” he says. Keinon watches each week’s Broncos game right after morning prayers on Monday morning — without knowing the score. When his sports buddies call, he answers with “Hi, don’t tell me who won.”

What has been difficult for American-born sports fans is to pass on a love of American sports to the next generation of children raised, if not born, Israeli. “My boys will amuse me by watching a few plays every now and then,” says Herb. “They do watch the Super Bowl with me though — but that’s because of the food spread.”

“Growing up here is different than there,” says Rabbi Dov Lipman, a native of Silver Spring, Maryland, where sports loyalties in those days stretched from Washington to Baltimore, encompassing the Redskins, Orioles, and Bullets. “There, it was every Sunday you go to school in the morning, come home, and sit from 12:30 ’til seven watching football. Night times for baseball. So my son, Shlomo, didn’t grow up with that culture of watching. He grew up watching highlights.”

And that, says Lipman, is fine.

“I did not want him to be, ‘Oh, I have to get up at 2 in the morning to watch the game.’ He’s a fan, he likes it, but he learns to live on the highlights and watching it that way.”

But more than sharing with Shlomo his love of baseball was the naches Lipman experienced watching his son pitch for the Israeli under-21 national team. The immigrant had arrived.

...........................

Loving sports may be universal. Most people have feelings about their home or national teams and athletes and the outcomes of the games they play. But Americans don’t seem able to get into Israeli sports. One reason is their unfamiliarity with soccer, Israel’s prime sport. Americans didn’t grow up with it, it’s not second-nature, and many don’t know the rules.

They are also unfamiliar with how sports leagues are played in the rest of the world, including Israel. Teams participate in multiple leagues or competitions simultaneously, such as the domestic league, a state cup tournament, and a European competition.

For religious Jews, there’s the issue of games being played on Shabbat. Baseball is an everyday sport, so missing a night game on Friday or a day game on Saturday is not crucial to following a sport in which teams play 162 games a season. The NFL for the most part plays on Sundays, so that is easy to follow. In Israel, most soccer games are scheduled for Shabbat, so religious fans cannot follow the games in real time.

There are also the different rhythms of the seasons to which immigrants are unaccustomed: soccer and basketball schedules here overlap almost completely, while football and baseball cross only two months of the year.

Then there’s politics: rivalries in Israel are shaded with biases remaining from the days when clubs formed in pre-state Palestine were offshoots of political movements. Sports teams named Beitar were once closely affiliated with nationalist right-wing Herut/Likud; Hapoel with Socialist left-wing Mapai/Labor. Hapoel wears red, Beitar yellow.

While identification with party has narrowed, the teams are still marked, at least to some extent, by their original cultural, political, social, and ethnic ideologies. Subsequently, rooting sentiments are different from what fans are used to in America, where loyalty is based by and large on geography — most sports fans in Pittsburgh or Cleveland like their town’s team.

Some immigrants are also turned off by the nature of the sports experience in Israel. The comportment at stadiums is more akin to the rowdy, male-centric atmosphere of European sports than the more family-oriented atmosphere in North America.

“Fan behavior plays a role,” says Benjamin Glatt, a native of Toronto, who nevertheless found his devotion across the Detroit River following the Motor City’s Red Wings and Tigers. “There has been behavior that I do not want my children to witness,” Glatt says. “Looking back at my North American experiences, which are plentiful, I am in no way willing to take children or myself to these types of venues.”

Susie Keinon concurs. “I wish there was better sportsmanlike conduct, specifically after a ‘bad’ call, or losing a game,” she says.

As for fans of professional basketball, a sport played in Israel and familiar to the American-born sports enthusiast, it’s not the same. From a sporting perspective, and with all due respect, the brand of game displayed here is not NBA-caliber basketball. It’s what an Israeli might call zoog bet — second-level quality (though certainly on a given night a top tier Israeli team could beat an NBA team, and has).

............................

All sports offer fans an escape, a pleasant diversion, and that is no different for American sports fans living in Israel. But for immigrants specifically, that diversion can trigger emotions that evoke a blissful time in another country. It’s a place they don’t mind revisiting.

“When I connect to my sports, I connect to the comfort and to the innocence of a great childhood that I had,” says Lipman, a Yesh Atid MK in the previous Knesset. “It’s not America, it’s just sports, and it’s something that brings me back there, to that innocent time, in the most beautiful ways. It’s to just enjoy — simply connecting to something fun and entertaining.” Moreover, says Lipman, “you grow up in the world of America, and you move to Israel — it’s difficult to completely separate yourself from everything you had growing up, to say to yourself, ‘I’m in a whole new life right now.’”

Some immigrants go completely the other way — the pride they feel being Israeli encompasses sports as much as anything else. “What sense does it make to get involved in every other aspect of Israeli life except sports, when I am an avid sports fan,” says Brian Freeman, a journalist, whose credentials as a passionate sports fan rooting for his native Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine are indisputable.

“Although I will never lose my connection to American sports, my desire for Israeli sports teams and individuals to succeed is much stronger,” Freeman says. “I don’t understand an American living here who is more devoted to his college team, where he attended for three or four years, but can’t, after three or four decades in Israel, build up a greater loyalty to whichever Israeli sports teams, or individuals, or national achievements strike his fancy. In individual sports — tennis, judo, sailing, Olympic medals — I always want an Israeli to beat out an American, or anyone else. Otherwise, what’s the point of being here?”

The problem, says Freeman, is not that someone follows sports from the old country, but that it’s done to the exclusion of Israel. “Sports is a part of the fabric of Israeli society,” he says. “The triumphs and heartbreaks of Israeli sports teams, or individuals in the Olympics, are just as strong as they are in the U.S., with its own history of failure, heartache, and thrill of victory that helps define Israeli culture. Anyone already following sports who doesn’t connect to Israeli sports is missing out on an important element of Israeli culture and cultural references — ‘We are on the map!’ being the most blatant, but by no means only example,” he said, referencing Tal Brody’s famous quip after his Maccabi Tel Aviv team won the 1977 European Cup Basketball Championship.

’’ All sports offer fans an escape, a pleasant diversion, and that is no different for American sports fans living in Israel. But for immigrants specifically, that diversion can trigger emotions that evoke a blissful time in another country. It’s a place they don’t mind revisiting.‘‘

Most Israelis become interested fans and root with national pride when an Israeli team competes internationally. The enthusiasm across the country for Maccabi Tel Aviv, an individual club, not an Israeli national team, is as momentous as if it is a national team when it’s playing well in a European tournament. “I remember when Maccabi Tel Aviv won its first European basketball championship after I made aliyah in ’96,” says Ron Dermer, a devoted fan of his hometown Miami Dolphins, referring to the Maccabi club facing Panathinaikos in the 2001 final. “It was a big deal.”

For American immigrants like Dermer, who has read the sports pages religiously every day since the age of eight, seeing newspapers put a sports story on page one — because the country is going gaga over an Israeli team — can be a welcome-to-Israel moment. “It was one of those moments when I felt most connected to Israel, when we had that kind of national celebration when Maccabi Tel Aviv won,” says Dermer, Israel’s ambassador to Washington. “And I’m a Jerusalemite, which probably means I wasn’t fully Israeli, because if you’re fully Israeli, no person who lives in Jerusalem would get excited about Maccabi Tel Aviv winning anything. But I felt deeply connected to the whole country.”

While Dermer says it’s exciting to root for Israel while watching the Olympics, he nevertheless retains an ongoing affection for his Dolphins and Heat, because that’s what he knows. “It’s like saying that you grew up loving a certain kind of music, and then all of a sudden you move to a new country and you forget about the music that you like,” he says. “It’s the same thing with sports.”

Freeman says it’s only natural for a Jew living in Israel to root for a Maccabi Tel Aviv team playing in the Euroleague, because the pride of being Israeli applies to sports as well. “Basketball is a sport we grew up with in the States, but here it’s ‘our guys’ wearing a uniform with the Star of David, going against the European giants,” he says. “And the same with the Israeli national team in basketball or soccer or any other sport.”

Freeman says that just as Israelis take pride in Israeli achievements in other fields such as drip irrigation, medical research, Iron Dome and others, “there is no reason those feelings of ‘us’ doing it should not apply to sports as well. Do you think that Abraham, when he made aliyah, kept allegiance to the Ur Idol Worshippers, and passed on his loyalty to his children? Or did he realize that Lech Lecha [God’s admonition to travel to Canaan] meant it was time to change his devotion to the Moriah Mountaineers and Shilo City Slickers?” ■

Elli Wohlgelernter is Night Editor at The Jerusalem Post. He made aliyah in 1991 and still misses his

Sundays off to be able to watch sports all day, but remains a devoted fan of the Yankees and Cubs.

UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS BY SARAH LEVI.

| PREVIOUS ARTICLE | NEXT ARTICLE |