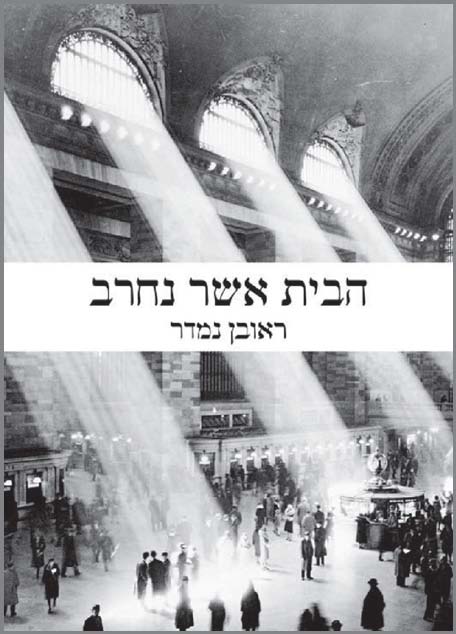

CONTACT Magazine is pleased to present an excerpt, in both Hebrew and English translation, of Reuven Namdar’s recent novel, The Ruined House, for which Namdar won the 2014 Sapir Prize, Israel’s most prestigious literary award. The protagonist of this novel, set in contemporary New York, is Professor Andrew Cohen, an American Jew, which is a first for a Hebrew novel written by an Israeli albeit one who makes New York his home. This is also the first time the Sapir Prize has been awarded to a writer living outside of Israel, making a statement about the possibilities of contributing to the development of the Hebrew language and its literature with experiences influenced by American Jewish life. The Hebrew of this work is rich in classical Jewish allusions in a way that stands in contrast with the standard fare of most contemporary Israeli fiction. As the Israeli expatriate literary community grows, the Hebrew language reflects broader Jewish sensibilities and has the potential to become more of a bridge than a divider. — David Gedzelman Reuven Namdar is a Hebrew author and translator who was born and raised in Jerusalem to a family of Iranian-Jewish heritage and now lives in New York City. His first book Haviv (a collection of short stories) won Israel’s Ministry of Culture's award for the best first publication of the year 2000. Azzan Yadin-Israel received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. He is a professor in the departments of Jewish Studies and Classics at Rutgers University. His most recent book is Scripture and Tradition: Rabbi Akiva and the Triumph of Midrash. (University of Pennsylvania Press). His articles are publicly available at Academia.edu. |

language The Ruined Houseby REUVEN NAMDAR. Translated by AZZAN YADIN-ISRAELOn a clear morning, on the sixth of Elul, in the year 5761 by the Jewish reckoning, corresponding to the sixth of September, 2000 AD, the gates of heaven opened above the great city of New York and, behold, all seven heavens were revealed through them, stacked one atop the other like the rungs of a ladder set upon the earth — squarely above the 4th Street subway station — the top of it reaching to heaven. Stray souls slipped phantom-like between the worlds, passing through like unnoticed specters, and among them a luminous, almost translucent figure — its form the form of a priest, on his head a linen headdress, and in his hand the golden firepan. No mortal eye beheld these sights; no one grasped the magnitude of this moment of divine favor in which all prayers are answered. Only an old homeless man, who lay filthy and bloated with hunger on the subway bench, half-hidden beneath a pile of rags, only he, who sought only to die, was abruptly gathered up to meet his maker, dying in a divine embrace. His dead face was frozen in a happy smile, the smile of one who has borne his iniquity and whose soul had completed its migrations and has been granted eternal rest. At that precise moment, not far away, in the recently constructed cafeteria of the Levitt Building, overlooking Washington Square Park, sat Professor Andrew P. Cohen of NYU’s Department of Comparative Cultural Studies. He was preparing the opening lecture for his course “Cultural Criticism or Culture of Criticism: An Introduction to Comparative Analysis,” a required course he offered every fall. Cohen was expert at crafting elegant titles for his creative and consistently overenrolled courses that drew students from a wide range of disciplines. The courses’ content, no less than their titles, was elegant — rounded ideas, brilliant and polished. They possessed, to be sure, real analytic force, but their true power lay in the exemplary beauty of the interpretive models they constituted: broadly relevant and masterfully presented, the models were easily grasped and easily assimilated. Indeed, “elegant” was the adjective most commonly associated with any and all matters that bore the mark and presence of Professor Andrew Cohen. Elegance permeated every aspect of his being: his physical appearance, his wardrobe, his body language and intonation, his writing and his ideas — all were governed by a gossamer, aristocratic lucidity that radiated a festive golden hue on everything it touched and stirred anyone who came in contact with him. Many had attributed this effect to Andrew’s “charisma” though they immediately recognized the inadequacy of the term. He possessed charisma, of course, a rare and supremely refined charisma, but there was something else, something elusive that resisted facile definition. One of his students, Angela Morenti, a brilliant young filmmaker specializing in advanced visual technologies, had once managed to capture in words what his presence evoked in her: “He has a halo.” She had said this in the cafeteria, right after the weekly graduate seminar in which a guest lecturer from Gender Studies examined the hidden gender biases of the virtual world. Cohen did not lead the discussion that week, but rather sat attentively with his students. “Look,” Angela explained to the doctoral student who had accompanied her on a covert smoking excursion, “I don’t mean ‘halo’” (her fingers signed scare-quotes in the air) “in the way new-age pseudo mystics use the term. It’s more of a cinematic halo, no — a television halo. It’s like when you bump into a celebrity, especially when they’re not in the spotlight, and you get a glimpse of their private lives, say, at a party or a restaurant or a gallery opening... they’ve got this halo, as if they still have their TV makeup on and the spotlight is shining on them — their skin glows, you know, it’s just radiant, and they...” Her voice trailed off. “Let’s just head back.” She flicked the burning cigarette butt on the sidewalk and headed back into the building, the doctoral student scurrying to keep up. “They don’t look real. Yeah, that’s it! They look fake! Like their own wax figures — like some glamorized representations of themselves, all illuminated and perfect. I guess that counts as some sort of achievement — to become an icon of yourself, a symbol of who you are, or, actually, of what you are. You know what I mean!” The young doctoral student, who, truth be told, had a little crush on both Angela and Andrew, nodded vigorously, though she wasn’t the least bit sure she knew. In honor of the new semester, Cohen was wearing a white morning-suit with a faux retro cut. On another man, it might have looked pretentious and distasteful. A green tie with scarlet embroidery rounded out the celebratory yet bemused look he favored. The same sophisticated, almost theatrical sartorial flair — a flair that scrutinizes its own limits, but always from a safe distance — was in evidence throughout: in his vintage wristwatch , the thick-rimmed, cartoonish reading glasses, and the Warholian shock of grey hair that lent his appearance a playful touch. The table at which he was seated was set at a slight remove from the others, framed by a bright triangle of sunlight that made it appear to levitate subtly . Two beautiful undergraduates, stared at him from afar and giggled, aflutter with admiration. Cohen smiled to himself as he leafed through his notes — he had grown accustomed to the warm caress of the female students’ adoring gaze. Yes, he could seduce more or less any female student he desired, but he was a man of strong moral convictions, who almost never deviated from the professional ethics that govern academic life. He continued to review the notes to his introductory lecture. He was not one of those professors who prepared obsessively before each lecture. He had full command of the material; his ideas were clearly structured; the position of teacher was natural to him. And besides, he was at his best when he improvised. ■ |

language

הבית אשר נחרב

מאת ראובן נמדר

בבוקר בהיר אחד, ביום ו’ באלול שנת ה”א אלפים שבע מאות שישים ואחת לבריאת העולם שחל להיות בשישה בחודש ספטמבר שנת 2000 למניין אומות העולם, נפתחו שערי השמים מעל העיר הגדולה ניו יורק וכל שבעת הרקיעים נגלו מבעדם, סדורים זה על גבי זה כשלביו של סולם הניצב ארצה, ממש מעל תחנת הרכבת התחתית של הרחוב הרביעי, וראשו מגיע השמימה. נשמות תועות חמקו להן בין העולמות, עוברות כצללים, וביניהן נרמזה דמות בהירה, שקופה כמעט — מראה איש כהן, ראשו צנוף במצנפת בד ובידו מחתה של זהב. עין אנוש לא שזפה את כל אלה ואיש לא הבין את גודל השעה, שעת רצון שבה מתקבלות כל התפילות כולן. רק כושי זקן אחד: חסר בית נְפוּחַ כָּפָּן ומזוהם ששכב מכוסה בסמרטוטים על ספסל בתחנה הרכבת ושאל את נפשו למות, נאסף באחת אל בוראו ומת מיתת נשיקה. חיוך מאושר נותר קפוא על פניו המתות, חיוכם של נשואי העוון שנשלם גלגולם וזכו במנוחת עולם. באותה השעה ממש, לא רחוק משם, בקפטריה האופנתית שהוקמה לא מזמן בלובי של בניין לויט ושחלונותיה השקיפו על וושינגטון סקוור פארק, ישב פרופסור אנדרו פ’ כהן, מרצה בכיר בחוג לתרבות השוואתית של אוניברסיטת ניו יורק והתכונן להרצאת הפתיחה של הקורס “ביקורת התרבות או תרבות הביקורת: מבוא לחשיבה השוואתית”, קורס חובה שאותו לימד, כמו בכל שנה, בסמסטר הסתיו. כהן התמחה במתן שמות אלגנטיים לקורסים שלו, קורסים יצירתיים ומקוריים שמשכו אליהם סטודנטים מכל החוגים ושהיו תמיד מלאים עד אפס מקום. לא רק שמות הקורסים היו אלגנטיים, אלא גם התכנים שנלמדו בהם — רעיונות עגולים, בהירים וחלקים שהיו אמנם בעלי כוח חדירה לא מבוטל, אלא שעיקר כוחם היה ביופיים ובמובהקותם של המודלים הפרשניים שאותם העמידו, מודלים תקשורתיים ומנוסחים להפליא שקל היה להיאחז בהם ולהפנים אותם. ובכלל “אלגנטי” היה התואר השכיח ביותר שהוצמד לכל דבר שבו ניכרו השפעתו ונוכחותו של פרופסור אנדרו פ’ כהן, כל הוויתו היתה כזו: מראהו ולבושו, שפת הגוף וטון הדיבור שלו, סגנון הכתיבה שלו, רעיונותיו — בכל אלה משלה איזו צלילות מעודנת, אריסטוקרטית, שצבעה בגוון זהוב חגיגי את כל מה שנגע בו והפעימה את כל מי שבא עמו במגע. רבים מאלה שחשו באותה התפעמות חגיגית בחרו לתאר אותה במושג “כריזמה”, אבל גם הם חשו מיד שהמושג לא מספיק קולע ונשמע בהקשר זה וולגרי מדי. כריזמה היתה לו, ללא ספק, כריזמה יוצאת דופן, מתוחכמת ודקה מן הדקה, אבל היה בו גם משהו נוסף, חמקמק, שקשה היה לתפוס במילים. אחת מתלמידותיו — אנג’לה מורנטי, קולנוענית צעירה וחריפה שהתמחתה בטכנולוגיות ויזואליות מתקדמות — הצליחה פעם ללכוד ולנסח במילים את התחושה שנוכחותו עוררה בה: “יש לו הילה”. זה היה בקפטריה, מיד אחרי הסמינר השבועי של תלמידי המחקר. כהן לא הנחה את הדיון באותו השבוע, הוא ישב עם תלמידיו והקשיב יחד איתם לדבריה של מרצה אורחת מהחוג ללימודי מגדר שהרצתה על ההטיות המגדריות הסמויות המצויות בסביבה הניטרלית- לכאורה של העולם הווירטואלי. “את רואה”, הסבירה אנג’לה לדוקטורנטית הממושקפת שהתלוותה אליה כשחמקה אל יציאת החירום של הקפטריה כדי לחטוף סיגריה אסורה, “זאת לא ‘הילה’” (אצבעותיה סימנו מירכאות כפולות באוויר) “מהסוג שהפסיאודו- מיסטיקונים נוסח העידן החדש מדברים עליה. זו הילה קולנועית, או יותר נכון טלוויזיונית. את יודעת איך שלפעמים את נתקלת בכל מיני מפורסמים, זה חזק בעיקר כשזה קורה מחוץ לאור הזרקורים, כשאת רואה אותם בנסיבות פרטיות: במסיבות, במסעדות, בפתיחות של תערוכות... ויש להם את ההילה הזו, זה כאילו שהאיפור הטלוויזיוני עוד מרוח להם על הפנים והזרקורים עדיין מכוונים אליהם — העור שלהם קורן, ממש זורח והם... בואי נחזור”.

היא השליכה את הבדל הבוער על הארץ ופנתה חזרה אל הבניין, הדוקטורנטית ממהרת אחריה. “הם לא נראים אמיתיים. זהו זה! הם נראים לא-אמיתיים! הם נראים כמו בובות שעווה של עצמם — כמו ייצוגים מושלמים, מְיוּפים ומוארים של עצמם. זה סוג של הישג, אני מתארת לי, להפוך את עצמך לאייקון של עצמך, לסמל של מי שאתה, או יותר נכון של מה שאתה. את יודעת על מה אני מדברת!” הדוקטורנטית, שהיתה מאוהבת קצת באנג’לה כמו שהיתה מאוהבת קצת גם בכהן, הינהנה בלהיטות למרות שלא היתה בטוחה כלל אם היא אכן יודעת.

לכבוד פתיחת הסמסטר לבש פרופסור כהן חליפת בוקר לבנה גזורה בסגנון כאילו-מיושן שהיתה עשויה, לו לבש אותה מישהו אחר, להיראות יומרנית מדי, סרת טעם. עניבה ירוקה, רקומה ארגמן, השלימה את המראה החגיגי, המבודח קמעה, אותו אהב לטפח. אותה מידה של תעוזה אופנתית מתוחכמת, ליצנית כמעט, הבוחנת מקרוב אבל ממקום בטוח את גבולותיה, אפיינה גם את שאר פרטי הופעתו: את השעון הישן שהיה ענוד על פרק כף ידו השמאלית, את משקפי הקריאה עבי המסגרת, הקריקטוריים, ואת הבלורית הוורהולית השופעת שהשיבה שנזרקה בה הוסיפה לה לוויית חן של קריצה. השולחן שאליו ישב היה מרוחק קמעה משאר השולחנות, תחום בתוך משולש בהיר של אור שמש שכמו הגביה אותו מעט מעל לרצפה. שתי סטודנטיות, צעירות ויפות, ליכסנו אליו מבטים מרחוק, התלחשו וציחקקו במבוכת הערצה. כהן חייך לעצמו תוך שהוא מעלעל ברשימותיו, הוא היה רגיל למגעם החמים של מבטי ההערצה של הסטודנטיות. הוא יכול היה מן הסתם לפתות כמעט כל סטודנטית שחשק בה, אבל הוא היה אדם בעל עמוד שדרה מוסרי חזק ולא חרג כמעט מעולם מתחומי האתיקה המקצועית. מבטו המשיך לרפרף על ראשי הפרקים של הרצאת הפתיחה. הוא לא היה מאותם מורים המתכוננים באופן אובססיבי לפני כל הרצאה והרצאה. הוא שלט בחומר שליטה מלאה, רעיונותיו היו סדורים יפה ועמדת המורה היתה טבעית עבורו לגמרי. וחוץ מזה, הוא היה במיטבו בזמן אִלתור דווקא. ■

| PREVIOUS ARTICLE | NEXT ARTICLE |